This is an example of the Delboeuf illusion, first identified by Belgian philosopher and mathematician Joseph Delbouef in 1887 or 1888. Modern psychologists have tested this illusion in various experiments, including one to determine if eyeshadow makes eyes look bigger (it does), and others to determine if the quantity of food on a plate looks. Nov 11, 2011 food, the dinnerware, and the tablecloth influences the Delboeuf illusion. This research is organized as follows. First, the Delboeuf illusion is introduced as a potential explanation for the link between the size of dinnerware and serving behavior and consumption. Second, four lab studies examine the opposing. A new study by Dr. Brian Wansink and Dr. Koert van Ittersum indicates that it does - or more specifically, that the color contrast between food and plate creates an optical illusion known as the Delboeuf illusion. Named after the Belgian scientist who discovered it in 1865. Jun 07, 2018 The Delboeuf Illusion can influence elderly food consumption because vision plays a huge role in our perception of food. It influences how much we eat. Vision even affects our perception of how we think the food tastes. A while back there were reports that using red plates for Alzheimer’s patients helped the elderly eat more food. The Delboeuf illusion appears within real-world decisional settings as well, such that adult humans overestimate food portions (e.g., amounts of cereal) presented in small dishware (assimilation.

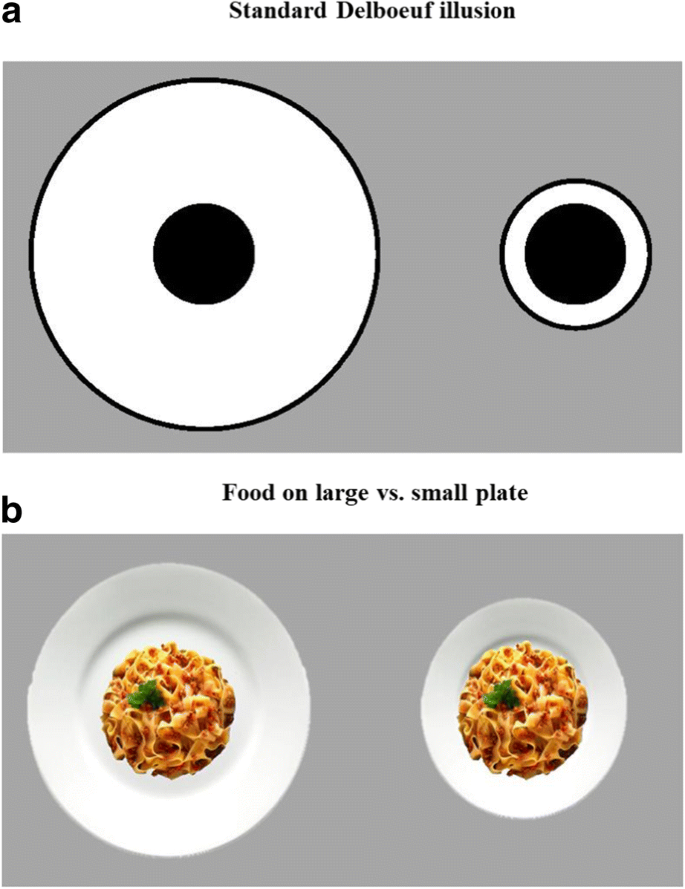

The Delboeuf illusion is an optical illusion of relative size perception: In the best-known version of the illusion, two discs of identical size have been placed near to each other and one is surrounded by a ring; the surrounded disc then appears larger than the non-surrounded disc if the ring is close, while appearing smaller than the non-surrounded disc if the ring is distant. A 2005 study suggests it is caused by the same visual processes that cause the Ebbinghaus illusion.[1]

Eponym[edit]

The illusion was named for the Belgian philosopher, mathematician, experimental psychologist, hypnotist, and psychophysicist Joseph Remi Leopold Delboeuf (1831–1896), who created it in 1865.[2]

Factors[edit]

According to Girgus and Coren (1982) the Delboeuf illusion uses both assimilation and contrast as elements in its perception distortion.[3] Assimilation is the predominant factor in the disc in the smaller outer ring (the example on the right in the image above). Girgus and Coren mentioned that this inner disc “tends to be overestimated” when compared to a regular disc without the additional concentric circle.[3] As the two circles are so close, they are perceived as a pair and the inner circle is overestimated.

The circle on the right however, will often appear smaller when compared to a simple circle of the same size. This is attributed to the contrast effect. The distance between the circles causes them to be perceived as separate and contrasting. The larger-circumference ring dwarfs the smaller central disc and causes it to be perceived as smaller.[3]

After a few minutes of looking at this illusion, the illusory effects diminish for human subjects.[3]

Studies regarding variations of the Delboeuf illusion found that when the outer circle is incomplete, the illusion is not as potent. When an additional circle was added surrounding the original two, the effect of the illusion was increased.[4]

Dieting and food perception[edit]

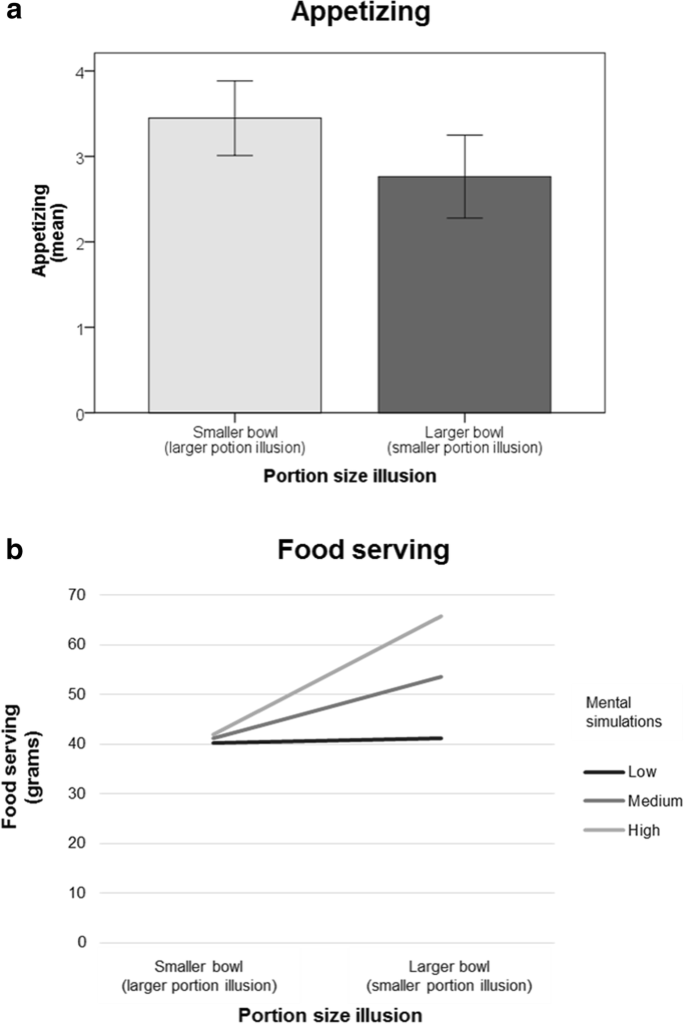

In 2012, Ittersum and Wansink published a study that hinted to the Delboeuf illusion as a factor in increased food servings. The study tested three different bowl diameters and measured how individuals served themselves differently depending on the bowl's diameter. The results showed that consumers poured 9.9% more soup in larger bowls, and 8.2% less in smaller bowls, as compared to the control bowls. It was mentioned that this reaction could be driven by the Delboeuf illusion.[5]

This illusion in connection to food however appears to be nuanced: Tzvi & Zitron-Emnual (2018) highlighted how effects of the Delboeuf illusion, when related to food items, is less potent when the participants are experiencing mild hunger. These researchers suggest that these findings are potential grounds for mitigating the use of the Delboeuf illusion as a dieting aid.[6]

Use in animal cognition[edit]

The Delboeuf illusion (often in connection with the Ebbinghaus illusion) has been used with great frequency in testing animal perception, since the ability to discern size seems highly relevant for many aspects of survival, particularly regarding food. The perception of the Delboeuf illusion differs greatly depending on the species.

Primates[edit]

Parrish & Beran (2014) found that chimpanzees would regularly select food platters that contained more food. Further testing showed that when chimpanzees were offered food on small and large plates, as they often picked the food on the smaller plate, even when the amounts were the same. This was discussed as a sign of the chimpanzee’s susceptibility to the Delboeuf illusion.[7]

A later study showed that capuchin and rhesus monkeys however, were unaffected by the illusion when asked to discriminate between the two circles. In contrast, when the illusion was later presented to the monkeys as part of an absolute classification task (deciding if the circles were 'big' or 'small'), both species reacted to the illusion and made selections that were much like the selections made by humans and chimpanzees.[8]

An attempt to run tests of portion discrimination in connection to the Delboeuf illusion on ring-tailed lemurs was unsuccessful; the lemurs' meal selections were not increased by a statistically significant degree by larger food portions, unless one option was nearly 40% larger.[9]

Dogs[edit]

Miletto-Petrazzini, Bisazza and Agrillo (2016) replicated the study conducted by Parrish and Beran (2014) but used dogs as the participants instead of chimpanzees. In this study, the dogs were allowed to select whichever food portion appeared larger as presented on larger and smaller plates. The response however was reversed from what humans usually exhibit: Dogs selected the meal presented on the larger plate most often. The authors went on to discuss how this may hint towards the dogs' reactions to the Delboeuf illusion as a matter of assimilated learning.[10]

Fish[edit]

Fish have been repeatedly studied as well to understand if they perceive the Delboeuf illusion. Fish trained to select larger center circles for reward, responded to the illusion differently depending on the species of fish. A 2008 study of damselfish illustrated that damselfish responded to variations of the Delboeuf illusion in a similar ways to humans and dolphins,[11] while guppies responded in reverse, selecting the circles with the larger annulus.[12]bamboo sharks did not generally make selections significantly higher than chance during the testing, and only showed preference to larger diagrams in general.[11]

Reptiles[edit]

Bearded dragons and red-footed tortoise were both studied to understand if these species can perceive the Delboeuf illusion. Bearded dragons showed action that suggests that they perceive the illusion in a way similar to humans. The tortoises however, showed no preference to larger portions (a similar problem found in the study of ring-tailed lemurs) and were thus not testable by the method that had been outlined by the test designers.[13]

References[edit]

- ^Roberts B, Harris MG, Yates TA (2005). 'The roles of inducer size and distance in the Ebbinghaus illusion (Titchener circles)'. Perception. 34 (7): 847–56. doi:10.1068/p5273. PMID16124270.

- ^Delboeuf, Franz Joseph (1865). 'Note sur certaines illusions d'optique: Essai d'une théorie psychophysique de la maniere dont l'oeil apprécie les distances et les angles'. Bulletins de l'Académie Royale des Sciences, Lettres et Beaux-Arts de Belgique (in French). 19: 195–216.

- ^ abcdGirgus, Joan S.; Coren, Stanley (1982-11-01). 'Assimilation and contrast illusions: Differences in plasticity'. Perception & Psychophysics. 32 (6): 555–561. doi:10.3758/BF03204210. ISSN1532-5962. PMID7167354.

- ^Weintraub, Daniel J.; Schneck, Michael K. (1986-05-01). 'Fragments of Delboeuf and Ebbinghaus illusions: Contour / context explorations of misjudged circle size'. Perception & Psychophysics. 40 (3): 147–158. doi:10.3758/BF03203010. ISSN1532-5962. PMID3774497.

- ^van Ittersum, Koert; Wansink, Brian (2012-08-01). 'Plate size and color suggestibility: The Delboeuf illusion's bias on serving and eating behavior'. Journal of Consumer Research. 39 (2): 215–228. doi:10.1086/662615. ISSN0093-5301.

- ^Zitron-Emanuel, Noa; Ganel, Tzvi (1 September 2018). 'Food deprivation reduces the susceptibility to size-contrast illusions'. Appetite. 128: 138–144. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2018.06.006. ISSN1095-8304. PMID29885383.

- ^Parrish, Audrey E.; Beran, Michael J. (2014-03-01). 'When less is more: like humans, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) misperceive food amounts based on plate size'. Animal Cognition. 17 (2): 427–434. doi:10.1007/s10071-013-0674-3. ISSN1435-9456. PMC3865074. PMID23949698.

- ^Parrish, Audrey E.; Brosnan, Sarah F.; Beran, Michael J. (October 2015). 'Do you see what I see? A comparative investigation of the Delboeuf illusion in humans (Homo sapiens), rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) and capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella)'. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Animal Learning and Cognition. 41 (4): 395–405. doi:10.1037/xan0000078. ISSN2329-8456. PMC4594174. PMID26322505.

- ^'Preliminary study to investigate the Delboeuf illusion in ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta): Methodological challenges'. Animal Behavior and Cognition. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ^Miletto Petrazzini, Maria Elena; Bisazza, Angelo; Agrillo, Christian (2017-05-01). 'Do domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) perceive the Delboeuf illusion?'. Animal Cognition. 20 (3): 427–434. doi:10.1007/s10071-016-1066-2. hdl:11577/3222731. ISSN1435-9456. PMID27999956.

- ^ abFuss, Theodora; Schluessel, Vera (2017-08-01). 'The Ebbinghaus illusion in the gray bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium griseum) in comparison to the teleost damselfish (Chromis chromis)'. Zoology. 123: 16–29. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2017.05.006. ISSN0944-2006. PMID28712674.

- ^Lucon-Xiccato, Tyrone; Santacà, Maria; Miletto Petrazzini, Maria Elena; Agrillo, Christian; Dadda, Marco (2019-05-01). 'Guppies, Poecilia reticulata, perceive a reversed Delboeuf illusion'. Animal Cognition. 22 (3): 291–303. doi:10.1007/s10071-019-01237-6. ISSN1435-9456. PMID30848385.

- ^Santacà, Maria Miletto; Petrazzini, Maria Elena; Agrillo, Christian; Wilkinson, Anna. 'Can reptiles perceive visual illusions? Delboeuf illusion in red-footed tortoise (Chelonoidis carbonaria) and bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps)'. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 133 (4): 419–427. doi:10.1037/com0000176. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

Delboeuf Illusion And Food Service

Delboeuf Illusion And Food

With the holiday season upon us – and all the festive food it brings – people should know that the color contrast between dinnerware and what's placed on top can affect how much we serve ourselves and consume, according a Georgia Tech College of Management researcher.

'Instead of scooping vanilla ice cream into a white bowl, you'd do better by your diet to pick a different color dish,' explains Koert van Ittersum, an associate professor of marketing at Georgia Tech, who conducted this research with marketing professor Brian Wansink of Cornell University.

Their study, published in the Journal of Consumer Research, sheds light on why people tend to over-serve themselves when given larger plates and bowls.

The researchers found that our susceptibility to over-serve ourselves has to do with the Delboeuf illusion, first discovered in 1865. This illusion leads people to perceive two identical circles positioned side by side as dissimilar in size if one is surrounded by a large circle and the other by a smaller circle. They perceive the latter as larger.

When it comes to dinnerware, this means that people (even expert nutritionists) tend to exceed a target amount of food (the inner circle) when the outer circle (the plate’s edge) is much larger in diameter.

The researchers found that diners can lessen the effects of this illusion by heightening the color contrast between their food and dinnerware. The study showed that experimental participants served themselves considerably more when they scooped white-sauce pasta onto a white plate than red-sauce pasta onto white dinnerware.

'White on white or red on red doesn't provide enough visual contrast between the target serving area and the outer edge of plate, increasing one's tendency to over-serve onto larger dinnerware and to underserve onto smaller dinnerware,' van Ittersum explains. “Those who own larger dinnerware in different colors may want to choose the color that highly contrasts with the food they are serving to minimize over-serving biases.'

While greater color contrast between food and plate can be beneficial to those watching their weight, over-serving tendencies also can be reduced by decreasing the contrast between dinnerware and tablecloth, the study shows. “If you place a white plate on a white tablecloth, the Delboeuf illusion is lessened because the outside circle essentially disappears and you only focus on the inside circle, which is the target food area,” van Ittersum explains.

For nearly 150 years, the Delboeuf illusion was regarded as of little practical value, note the researchers in the study, titled “Plate Size and Color Suggestibility: The Delboeuf Illusion’s Bias on Serving and Eating Behavior”

“In the context of serving behavior, however, it takes on an undiscovered dimension of every importance….,” they write. “Over time and time with repeated meals, the gradual impact on one’s weight gain would be significant.”

Just understanding the phenomenon of the Delboeuf illusion probably isn’t enough to visually compensate for its effects, they say. “In the midst of hard-wired perceptual biases, a more straightforward approach would be to simply eliminate larger dinnerware – replace our larger bowls and plate with smaller ones or contrasting ones,” write the researchers.

CONTACTS